Capitalism – Don't throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Life is good on paper in many ways. Contrary to what our fear-mongering media, and eyeball seeking algorithms are telling us, we’re living in a time of relative abundance and safety compared to previous times. The average person living in an economically developed country lives a more comfortable life than a medieval king. We have hot showers, affordable air travel, cryptography, nanotechnology, access to more information than is possible to comprehend in the literal palms of our hands, you name it.

Aside from the sheer willpower of people working together to push for political change, technology has been more instrumental than anything else in elevating the freedom and agency of people worldwide, and more broadly the advancement of humanity. The mainstream discourse is full of stories of how the use of encrypted messaging and other privacy tech for example, has circumvented authoritarian regimes and allowed freedom and prosperity to flourish. We fervently celebrate the legacy of figures who fought for our human rights as we should, as well as those who have pioneered freedom technology. But there seems to be little talk about the really fundamental concepts that are key to our prosperity, mainly because they’ve sadly become divisive. I’m talking about our economies and how we run them. The various approaches that are rooted in political ideology—socialism, communism. Capitalism.

Capitalism—the notion of free enterprise along with the use of money as a medium of exchange and private property rights, has been the most persistent economic system throughout history. The ever-present blueprint that dictates how we distribute resources amongst each other.

In the current time of relative wealth and individual agency but a hard-to-pinpoint feeling of malaise in society, we seek a fundamental scapegoat. That often is capitalism. Anti-capitalist and pro-socialist sentiment seems to be on the rise in universities, activist groups, consultancies, the liberal media and high street bookshops, where flashy covers that wish for death to capitalism are displayed front and centre alongside copies of the latest Dan Brown or James Patterson.

Many people, particularly, students and young adults gravitate towards cultural movements, slogans and political candidates that are cosy to socialism and hostile to capitalism. Like the flag of the sovereign nation is often adopted by the right as a symbol that reflects their crusade, symbols like the hammer and sickle, and elements of language such as political candidates calling their supporters “comrades” are adopted, which are explicit references to communism—the extreme rejection of capitalism and private property rights in favour of equality, altruism, co-operation and centralised planning to achieve those ends.

In the debate about what system benefits the collective good, socialism may have better, and more appealing optics on the surface, because it addresses the economic imbalance in our society more directly, and perhaps intuitively through the redistribution of wealth. More money for the impoverished and vulnerable, less for the wealthy.

Capitalism on the other hand allows resources and wealth to be distributed by the mechanisms of the market. It is seen as a system that is to some extent unbalanced and exploitative, the unregulated free market which capitalism is predicated on allowing some people to become disproportionately more wealthy than others. Aligning with that caricature we’ve all grown up with, of a man with a top hat, moustache and a waistline that suggests over-indulgence at the expense of honest hard working people. We conjure images in our minds of these greedy, grotesque fat-cats hoovering up all the resources and leaving everyone else with nothing but scraps to fight over.

Putting aside the persuasive power of political satire, and to look at things objectively, capitalism is a system fueled by individual self interest. A system based on greed surely can’t work for the public good.

Or can it? This is my attempt to shine some light through the dust kicked up by the ongoing war of ideals. To peel back the endless layers of abstraction and distortion piled on by the media, algorithms and political institutions and to look at what capitalism is from the lens of first principles, and how these economic philosophies align with how we actually think and act. Because as they say. Actions speak louder than words.

First principles

Capitalism is where people have the freedom to sell what they like for the price they like. When money made is in excess of the input costs, the difference can be kept, which can then be spent to satisfy own needs and wants. The notion of trade, which is to transfer ownership of something for something else is predicated on private property rights. Without this, there is no peaceful exchange, only theft. Capitalism also requires a market largely free of intervention by non-productive interests (such as government and regulators) to maintain a competitive environment and prevent monopolies forming.

With this simple foundation in place, elements of capitalism materialise through competitive dynamics. Market efficiency increases when competition between suppliers chase down prices, providing more value for the consumer. Hard work and risk management is rewarded with profit, whereas a lack of market research and poor execution leads to loss and capitulation to new participants who are not restricted in any way to compete, this competitive environment drives creative destruction, where outdated businesses that struggle to move with the times get disrupted by more creative and agile businesses who know how to provide much more value to consumers.

Price (controls)

Price is a particularly interesting thing to think about. Prices are much more than numbers next to products. It is a communication medium that signals what people really value in real time. If people aren’t buying, suppliers respond by reducing prices until they are buying again. This equilibrium settles at the point where the supplier is able to make a worthwhile profit, and the consumer gets their goods at a cost that is affordable to them. Prices are also a great communicator of supply shortages. If there’s a badly performing crop of bananas for example, the price increases to a point where the demand meets the supply.

In this way, prices form organically, in a decentralised way, efficiently communicating the intricacies of what people value. The need for this natural feedback mechanism of pricing, to establish a healthy economy cannot be understated, as it distils down trillions of individual decisions—the physical cost to the supplier to produce the item against the judgments made by consumers that express how much they value it—into a simple, single thing. A number.

The different approaches to finding this number is where I’m going to lay out my first comparison between capitalist economies and centrally planned socialist ones, it’s based on the premise that value is entirely subjective. One mans trash is another mans treasure. And this is relevant to our current political environment where some politicians are appealing to the voter base for the establishment for things like price controls.

Price controls are disastrous for economies, not just because it places the burden of having to figure out the prices of products onto the shoulders of the central planners, but it allows for coercively dictating what people should value based on their imposed virtues or ideology. The advocacy of this is at best naive at worst purposefully authoritarian.

Regardless, in practical terms, central planners would never be able to establish pricing across an economy due to the sheer complexity and enormity of the task, nor would a central planner with any kind of conscience want to be burdened with it. Too hard a push of the metaphorical supply lever would lead to the environmental degradation caused by overproduction, too much of a yank would lead to under-production, where basic needs would be unmet, resulting in famine and other forms of extreme hardship.

But in a free market capitalist system, where prices can freely adjust, pricing ensures resources are efficiently allocated. As French economist Jean-Baptiste Say alludes to, there cannot be sustained overproduction or underproduction of a natural resource as long as prices are allowed to adjust. If the farming and distribution of wheat is becoming too resource intensive, the price of bread will naturally increase to reflect this, incentivising consumers to find other products to satisfy their need for carbs (sweet potato maybe?), resources which might be in much greater abundance in nature.

Under price controls imposed by a centrally planned socialist economy, this adjustment cannot happen. The price of bread would be artificially suppressed, and suppliers would need to be subsidised by the government to keep their supply moving despite the increased resource requirement to do that. Without the subsidies, there would be no incentive for suppliers to remain in business, as they would be operating at a loss. Eventually the provision of bread and other vital products falls under the control of the state.

Any amount of centralised capture of the economy results in distortion of price signals. Total capture of the means of production from private ownership results in the state becoming both the seller and buyer, and prices lose all meaning in this system as does any hint of an economy.

“With no ownership there is no exchange. With no exchange there are no prices. With no prices there is no economic calculation and without economic calculation, there is no economy.” Ludwig von Mises

With no economy, it is entirely up to the state to provide the people with their wants and needs. The satisfaction of which, to the individual is dependent on the state agreeing they should need or want those things, and the state actually being able to provide them. Without the price signals, there would be no means to make this economic calculation, and without that, production decisions would be made in the dark.

Austrian economist Friedrick Von Hayek outlines the need for pricing in his essay The Use of Knowledge in Society. Arguing that knowledge is decentralised, and exists in inaccessible fragments. People have vastly diverse needs and desires that without prices, cannot be predicted or modelled with any kind of accuracy in order to make the necessary economic calculations. Hayek also argues in favour of the agency of the individual, and his or her ability to make economic decisions based on what they know, challenging the assumption of the socialist, that the central authority must know better. Along these lines we can say that prices in a free market capitalist system is a direct reflection of individuals’ freedom of expression, and control of prices is a censorship of this right.

Incentives

Talk is cheap, another popular trope that helps us understand the distinction between capitalism and centrally planned economic systems like socialism. It is relatively easy to talk a system into some kind of existence, and justify it based on moral platitudes which few people will argue with. Economists and philosophers have long produced texts about their favoured economic models, which have been celebrated by idealogues who often fail to acknowledge a simple inescapable truth. That human action is almost entirely driven by one thing—self-interested incentives.

A slogan that encapsulates Marxist theory, From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs is based on the idea that everybody will always sacrifice their time, energy and unique skills, not for any kind of personal gain but out of pure altruism and the good of the collective. This makes assumptions that are out of whack with how we actually think and behave as human beings. So if we were to start all over again, and adopt an economic system that will be willingly adopted, ignoring incentives would be ideological. This sounds obvious, but it is quite surprising how much we lean towards systems that appeal to our well-meaning virtues above practical application.

Capitalism closely aligns with human incentives. The incentive for profit to the supplier, and the value to the consumer. This interplay of incentives allows resources to be efficiently allocated to where they are valued. Not through charity or coercion at the hand of central planners, but self interest.

The idea that incentives driven by self-interest can benefit the collective has been written about extensively. Scottish economist Adam Smith wrote in his seminal work, Wealth of Nations (1776) “It is not from the benevolence of the Butcher, the Brewer or the Baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest”

In the same book, Smith used the metaphor The Invisible Hand in an argument against government regulation of markets. It has been often used by economists and philosophers to describe the spontaneous order that arises from a free market capitalist system. How equilibrium between supply and demand is achieved not through centralised control but a seemingly unseen force.

Misaligned incentives

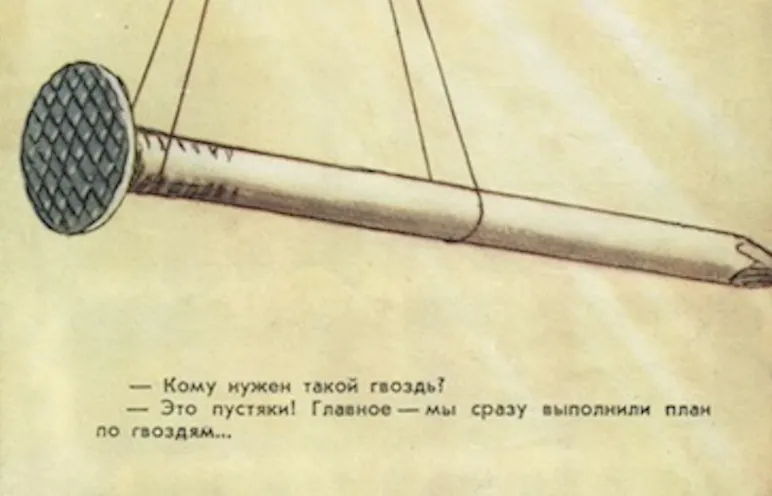

The One big nail problem based on a cartoon that appeared in the Soviet magazine Krokodil in 1957, outlines the absurdity of central planning and how it ignores human incentives. A factory in Soviet Russia receives its quota to produce a set number of nails. The incentive for the factory workers is to produce the nails as quickly as possible so they can achieve their quota and go home early. They achieve this by producing extremely small nails which aren't useful for anything. When the state gets wise to this, they say the nails must meet a certain weight, so they produce one big nail which unsurprisingly is also is not useful for anything.

Factory worker: Who needs a nail like this? - Manager: That’s irrelevant, what matters is that we have fulfilled the plan target! I don’t know how the story ends but I’d assume the factory manager was sent to the gulag.

This phenomenon describes Goodhart's law, which states When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure socialism is predicated on these kinds of performance targets that misalign incentives.

In capitalist systems run by governments with socialist tendencies, these targets are often set through programmes that sound great on paper but, like oil and water, don't mix with incentives. An example of this which is even more laughable than the One big nail problem, because it’s real , is the governments ambitious programme to roll out 4G mobile connectivity to 95% of the land area of Britain. Of course this led to companies fighting to build telecommunications infrastructure in areas where land is the cheapest. Such as the most remote parts of Scotland, so sheep and passing deer become the first recipients of reliable mobile network connectivity.

Again, it is human nature to chase incentives. Governments intervene, more often than not with good intentions, but misaligned incentives can result in outcomes that are at best ineffective or at worst, profoundly damaging to society, even precipitating wars, as is evident through the manipulation of money by governments and central banks.

Monetary interventionism is a deep topic that goes beyond the scope of this article, but is dug into comprehensively in Seb Bunney’s book The Hidden Cost of Money (2023). Seb identifies what he calls the four stages of economic ruin, which goes into how intervention in money and the economy skews our incentives for the worse, affecting our behaviour, relationships and society.

The socialist utopia

One of the themes of this article is how we think and act as humans, and asserts that humans will always act out of self-interest. Mises who argues in his book Human Action (1949) that self-interest is a universal axiom of human behaviour, even that altruism is an expression of self-interest.

Sir Thomas More’s book Utopia (1516) which is known to have inspired the work of Marx, Engels and other prominent socialists, envisions a society where the sins of greed and envy (More was a devout catholic) are rooted out through practices like casting precious metals into mundane items to remove their prestige, and forcing everyone to change their house every ten years, so they don’t develop a sense of pride of possession or ownership. With the assumed conformance to the set of rules, people have to only work a couple of hours a day to satisfy collective needs and have unrestricted access to stored provisions. Such a socialist utopia relies on absolute conformance with the rules, and the fundamental challenge with socialism, or collectivism is to align the interests of all subjects away from the self and towards the collective. The natural question is, how can this work in practice?

The influential social reformer Robert Owen suggested human nature is not fixed but entirely shaped by environment, his belief was that if a person is removed from the competitive capitalist environment, into an egalitarian co-operative one, they will let go of their self-interests entirely in favour of the collective.

A socialist utopia would rely on Owen’s theory being universally true, as if it wasn’t, conformance would have to be enforced through the threat of violence, or maybe enslavement with gold chains and shackles. Yes, slavery as a means of punishment was a dark addition to More’s utopia.

Owen actually tested his theory when he attempted his utopian town in Indiana, which he named the New Harmony Community of Equality, where anyone and everyone would be welcomed, such was his liberal ideals. The majority who shared his vision were disrupted by the “free-loaders” who Owen anticipated would be reformed—continue to, well free-load. Owen’s son, William, who he left to oversee the community reflected in his diary that the experiment attracted “crackpots, free-loaders, and adventurers whose presence in the town made success unlikely.”

Ultimately co-operative socialist societies will fall apart when the natural human tendency towards individuality, self-expression and self-interest takes hold in enough of the people, to fracture the system that relies on total suppression of those tendencies.

If people did conform to the set of rules, it can be argued that it would struggle to advance from being an agrarian society where—not having the environment to allow for innovation and creative destruction, only incremental improvements can be made to primitive technology.

Most utopian socialist thinkers appeared to have little acknowledgment of the need for specialisation among the working people, nor for technological advancement. In More’s utopia working people would rotate trades, like they would rotate houses, to prevent hierarchy and inequality forming. Another utopian socialist thinker, Charles Fourier envisaged the Phalanstery a kind of commune of working people who would swap trades as their interests piqued and waned, according to the principle of “attractive labour” he theorised people will always be incentivised to work if their work engages their talents and interests, and doesn’t become monotonous.

Work and the division of labour in a capitalist system is far from the palliative approach used in the socialist utopia. Like how sunlight, water and nutrients give root to complex natural ecosystems like forests—the right to free enterprise and private property give root to something which a planned socialist society would never be able to—the spontaneous emergence of specialisation among the people.

To detail how specialisation leads to a healthy economy and rapid technological advancement, we can imagine a humble baker, whose bakery, though popular, is often closed because the baker has to spend a lot of time maintaining the ovens. Something which she is not very good at, not being mechanically minded. Meanwhile an enterprising mechanic notices the bottleneck. He starts up a new business maintaining ovens, which becomes so successful he’s able to employ a team of mechanics. The baker, now free to focus on what she’s particularly good at, is able to scale up her business and employ her own team of bakers. This means more people are on their feet and wearing out their shoes. Sam the shoesmith now has a queue of people outside his shop and he’s able to raise his prices, that is until a local entrepreneur noticed the queues outside his shop and the high prices he’s charging. Her particular shrewdness in business and inclination towards entrepreneurship lead her to invent a way shoes could be fixed much quicker and cheaper. A rich, diverse and vibrant local economy takes root through the incentive of self-interest.

It's clear to see that, if you can imagine two parallel societies—one adopting utopian socialism, and the other capitalism, getting shipwrecked on identical islands with the same resources—the capitalist one would reach Mars before the socialist one would invent the horse-drawn plough.

This unapologetically cynical take on the socialist approach to the division of labour is based on the whimsical form of socialism imagined by the early utopian thinkers, who theorised people would be productive based on flimsy assumptions about how they are incentivised. Actual socialist states like the USSR used the threat of violence and imprisonment to make sure people turned up at factories from one end of the vast Soviet expanse to the other to grind out days of mundane soul-crushing labour. Only through brutal totalitarianism, was a centrally planned socialist state able to become a technological superpower. One that rivalled the capitalist Western bloc during the cold-war.

The incentive for peace

Unlike the Stalinist form of socialism, capitalism incentivises productivity based on voluntary participation over coercion. The pioneering engineers of the Buran space shuttle turned up to work because they wanted to sleep the next night in their state provisioned Stalinka apartment rather than the far less palatable state prison.

Their counterparts across the Pacific, working on their own shuttle, were under employment contracts which they could voluntarily terminate. Not that they would have wanted to. A job at NASA was like hitting the jackpot. A massive house in the suburbs, paid off in just a couple of years, a car and all the prospects to start a big family. The American dream as it was.

When we think about another way free enterprise and the recognition of property rights fosters relationships that would otherwise be violent or coercive, we need to go back further than the Buran, Owen’s doomed-to-fail New Harmony community and More’s utopia, to pre-historic times before even money was invented.

In this time the only way to settle trade was barter and other kinds of reciprocal exchange arrangements. These were only possible when very specific conditions were in place. When they no longer were, the only moves left in the fight for scarce resources was violence, coercion and subjugation. A brutal zero-sum game where the victor gets all the spoils at the expense of the loser.

But when adversarial tribes found they could trade with each other, by settling on a mutually valuable medium of exchange, the need for violence would be negated, as both parties get what they need and are able to continue to exist. In fact it would become more beneficial to them that their neighbour continues to exist and prosper, to maintain a mutually beneficial trading arrangement. Instead of ripping each other's heads off and putting them on sticks for decoration, they would share wealth and prosperity. The more tribes see eachother as trading partners, the faster the collection of disparate warring tribes converge into civilisations. To this day, cross-border trade is the most effective means for peace. Countries don’t tend to drop bombs on those which they have trading relationships with.

A look to nature

Growing up with nature programmes that often depict predation, where one preys on another to survive, we can be forgiven for thinking we’ve outsmarted nature with our complex and mostly peaceful interactions. But there are many complex and mutually beneficial relationships in nature too. Bees and flowers, ants and aphids, Oxpeckers and Rhino’s. Nature's ecosystems are not unlike free market capitalist economies. But there are few more fascinating than the relationships between Mycorrhizal fungi and plants.

Many types of plants are not at all self-sufficient. To sustain themselves they need certain nutrients which they aren’t able to obtain themselves. Underground Mycorrhizal fungal networks are made up of thread-like links that intertwine with the roots of the trees and form connections.

The two organisms engage in mutually beneficial trade. The tree is very good at producing sugar from carbon in the air through photosynthesis. The fungi is very good at breaking down different kinds of matter deep in the soil, to extract a host of different nutrients. The fungi and the plant cells are able to communicate with eachother through chemical interactions, signalling to the other exactly what type of nutrient it wants. If one type of fungi isn’t able to provide it, the plant cells will signal to one that is able to, so a trade can happen.

It is interesting to think that our desire to distribute resources with eachother through trade and self-interested incentives might be a natural instinct. Maybe we landed on the principles of capitalism before it even had a name, and the spontaneous order driven by self-interested incentives is the natural universe-given instinct of all beings.

No perfect system

Capitalism is not the perfect system, because a perfect system doesn’t exist. A pessimist would say it’s the least worst system. It is rough and messy and often results in painfully unequal outcomes, but it is only as healthy or sick as the environment and external factors dictate it to be. It can be weakened by state imposed forces like over-regulation, the socialisation of the economy and the dark forces of our credit based, inflationary monetary and banking system, that turn our vibrant and healthy economies into something that is only vibrant and healthy by illusion—the injection of fake money into the economy is the real poison in the well. The money that is not earned through the creation of value, but the artificial materialisation of new money by banks, and the hoarding of wealth by those who are closest to the taps. It is wise to acknowledge that the real problem is money, at least the form of (fiat) money we use now—and not conflate the problems afflicting our advanced economies and societies with the very thing that advanced them there in the first place.

Capitalism is the independent coffee shop, the small family-run butchers, the farmers market, the artist, the architect, the guy selling burgers from a food truck. The entrepreneur figuring out how to deliver more value for less cost. It is the decentralised framework with which resources are efficiently distributed. In tackling inequality, power structures and general malaise in society, it is important we are not advocating for something that could be far worse for far more people. Yet another popular trope fits. Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. Alarmingly prescient in these times.

The next part of this series will look at how broken money is breaking the world. And my thesis for Fix the money, Fix the world.